Author

This is a guest blogpost contributed by Alibaba Group’s Machine Translation Platform team and PAI-Blade team

Background

Neural Machine Translation (NMT) is an end-to-end approach for automating translation, with the potential to overcome the weaknesses in conventional phrase-based translation systems. Recently, Alibaba Group is working on deploying NMT service for global e-commerce.

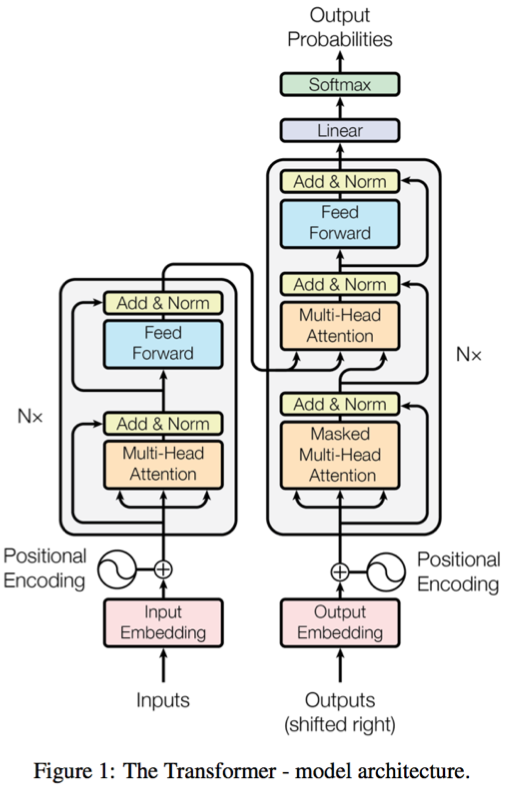

Currently we are exploiting Transformer [1] as the major backbone in our NMT system since it is more friendly for efficient offline training with on-par (even higher) precison against classical RNN/LSTM-based models. Although Transformer is friendly for the offline training phase as it breaks the dependencies across time steps, it is not quite efficiency for online inference. In our production environment, it has been found that the inference speed of the intial version of Transformer is around 1.5X to 2X slower than that of the LSTM version. Several optimizations have been undertaken to improve the inference performance, such as graph-level op fusion, loop invariant node motion [3]. One paricular challenge we observed, is that batch matmul is a major performance hot-spot in Transformer and the current implementation in cuBLAS is not well optimized.

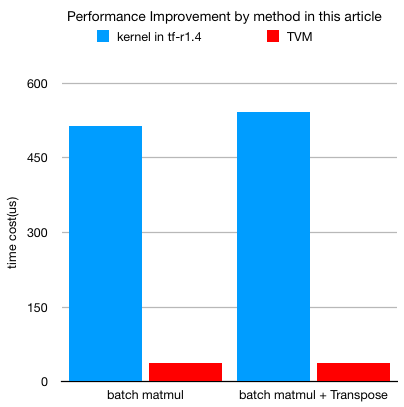

The results below show that TVM generated kernel (with schdule optimization) brings at least 13X speed-up for batch matmul computation, and a futher speed up with operator fusion enabled.

Batch Matmul

Why batch matmul

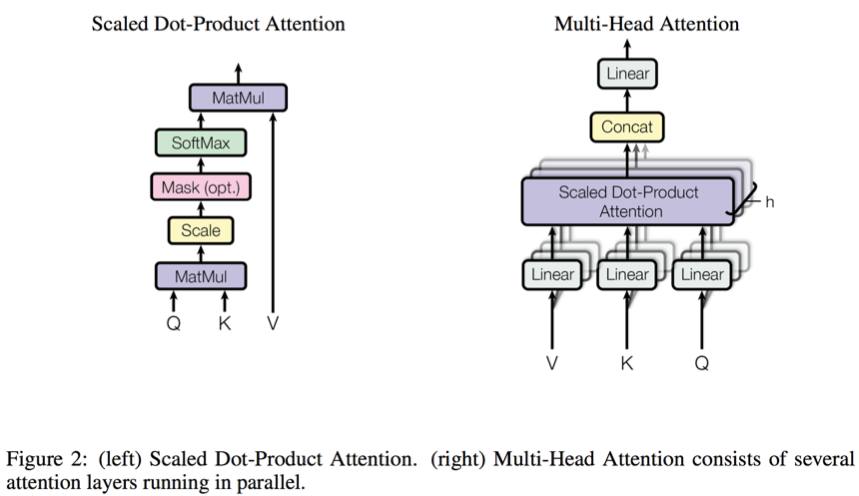

In Transformer, batch matmul is widely used in the computation of multi-head attention. Using batch matmul, multiple heads in the attention layer can run in parallel, which can help improve the computation efficiency of the hardware.

We conducted a thorough profiling of the Transformer model in the inference phase, and it is shown that batch matmul computation contribute up to ~ 30% of GPU kernel execution time. Using nvprof[2] to do some first-principle analysis of cuBLAS’s batch matmul kernel,it is clearly indicated that current implementation is quite under-performing and several interesting phenomena are observed.

What is batch matmul

Typically, a batch matmul computation performs the matrix-matrix multiplication over a batch of matrices. The batch is considered to be “uniform”, i.e. all instances have the same dimensions (M, N, K), leading dimensions (lda, ldb, ldc) and transpositions for their respective A, B and C matrices.

Batch matmul computation can be described more concretely as follows:

void BatchedGemm(input A, input B, output C, M, N, K, batch_dimension) {

for (int i = 0; i < batch_dimension; ++i) {

DoGemm(A[i],B[i],C[i],M,K,N)

}

}

Batch matmul shapes

In the language translation tasks, shape of the batch matmul is significantly smaller than normal matmul computation in other workloads. The shape in Transformer is relevant to the length of input sentences and that of decoder steps. Normally, it is smaller than 30.

As to the batch dimension, it is a fixed number given a certain inference batch size. For instance, if 16 is used as batch size with beam size being 4, the batch dimension is 16 * 4 * #head (number of heads in multi-head attention, which is usually 8). The shape of the matrix M, K, N are within the range of [1, max decode length] or [1, max encode length].

Performance issue of cuBLAS’ batch matmul

Firstly, we make a theoretical FLOPs analysis over the batch matmul kernels. The results are quite interesting: all the batch matmul have limited computation intensity (less than 1 TFLOPs).

Then we profile the cuBLAS performance of batch matmul with multiple shapes through nvprof. The table below shows some of the metrics obtained on a NVIDIA M40 GPU with CUDA8.0.

| input shape [batch, M, N, K] |

kernel | theoretical FLOPs | nvprof observed FLOPs | theoretical FLOPs / observed FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [512, 17, 17, 128] | maxwell_sgemmBatched_128x128_raggedMn_tn | 18939904 | 2155872256 | 0.87% |

| [512, 1, 17, 128] | maxwell_sgemmBatched_128x128_raggedMn_tn | 1114112 | 2155872256 | 0.052% |

| [512, 17, 1, 128] | maxwell_sgemmBatched_128x128_raggedMn_tn | 1114112 | 2155872256 | 0.052% |

| [512, 30, 30, 128] | maxwell_sgemmBatched_128x128_raggedMn_tn | 58982400 | 2155872256 | 2.74% |

Even with different shapes (varing in M, N, K), all the maxwell_sgemmBatched_128x128_raggedMn_tn calls execute the same amount of FLOPs, which is much bigger than the theoretical value. It can be inferred that all these different shapes may be padded to a certain shape. Among all these shapes, even in the best case, the theoretical FLOPs is still only 2.74% of the actually executed FLOPs, therefore most of the computation is quite redundant. Similarly, the calls of another cuBLAS kernel maxwell_sgemmBatched_64x64_raggedMn_tn show the same phenomena.

It is obvious that cuBLAS’ batch matmul implementation is far from efficiency. Thus we use TVM to generate efficient batch matmul kernels for our NMT workloads.

Batch matmul computation

In TVM, a general batch matmul computation can be declared as:

# computation representation

A = tvm.placeholder((batch, M, K), name='A')

B = tvm.placeholder((batch, K, N), name='B')

k = tvm.reduce_axis((0, K), 'k')

C = tvm.compute((batch, M, N),

lambda b, y, x: tvm.sum(A[b, y, k] * B[b, k, x], axis = k),

name = 'C')

Schedule optimization

After declaring the computation, we need to devise our own schedule carefully to squeeze performance potential.

Tuning parameters of block/thread numbers

# thread indices

block_y = tvm.thread_axis("blockIdx.y")

block_x = tvm.thread_axis("blockIdx.x")

thread_y = tvm.thread_axis((0, num_thread_y), "threadIdx.y")

thread_x = tvm.thread_axis((0, num_thread_x), "threadIdx.x")

thread_yz = tvm.thread_axis((0, vthread_y), "vthread", name="vy")

thread_xz = tvm.thread_axis((0, vthread_x), "vthread", name="vx")

# block partitioning

BB, FF, MM, PP = s[C].op.axis

BBFF = s[C].fuse(BB, FF)

MMPP = s[C].fuse(MM, PP)

by, ty_block = s[C].split(BBFF, factor = num_thread_y * vthread_y)

bx, tx_block = s[C].split(MMPP, factor = num_thread_x * vthread_x)

s[C].bind(by, block_y)

s[C].bind(bx, block_x)

vty, ty = s[C].split(ty_block, nparts = vthread_y)

vtx, tx = s[C].split(tx_block, nparts = vthread_x)

s[C].reorder(by, bx, vty, vtx, ty, tx)

s[C].reorder(by, bx, ty, tx)

s[C].bind(ty, thread_y)

s[C].bind(tx, thread_x)

s[C].bind(vty, thread_yz)

s[C].bind(vtx, thread_xz)

We fuse the outer dimensions of the batch matmul, i.e. the BB and FF of the op’s dimension, normally known as “batch” dimension in batch matmul computation. Then we split the outer and the inner dimensions by a factor of (number_thread * vthread).

Strided pattern is not needed in batch matmul, thus the virtual thread number (vthread_y and vthread_x) are both set to 1.

Finding the best combination of number_thread

The results below are obtained on a NVIDIA M40 GPU device with CUDA8.0.

| Input Shape [batch,features,M,N,K] | num_thread_y, num_thread_x | num_vthread_y, num_vthread_x | Time(us) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [64,8,1,17,128] | 8,1 | 32,1 | 37.62 |

| [64,8,1,17,128] | 4,1 | 32,1 | 39.30 |

| [64,8,1,17,128] | 1,1 | 32,1 | 38.82 |

| [64,8,1,17,128] | 1,1 | 256,1 | 41.95 |

| [64,8,1,17,128] | 32,1 | 1,1 | 94.61 |

As learned from past experience, the method to find the best combination of num_thread_y and num_thread_x is through brute-force search. After a brute-force search, the best combination for current shape can be found, which in current computation is num_thread_y = 8 and num_thread_x = 32.

Fuse batch matmul with other operations

Normally, the existing “black-box” cuBLAS library calls play the role as the boundary of the normally used “op fusion” optimization tactics. However, with the generated efficient batch matmul kernel, the fusion boundary can be easily broken, more than just element-wise operations can be fused, thus futher performance improvement can be obtained.

It is observed from the the computation graph that a batch matmul is always followed by a broadcast add operation or a transpose operation. By fusing “add” or “transpose” operation with batch matmul, kernel launch overhead and redundant memory access time can be reduced.

Batch matmul and broadcast add fusion computation can be declared as follows:

# computation representation

A = tvm.placeholder((batch_size, features, M, K), name='A')

# the shape of B is (N, K) other than (K, N) is because B is transposed is this fusion pattern

B = tvm.placeholder((batch_size, features, N, K), name='B')

ENTER = tvm.placeholder((batch_size, 1, M, N), name = 'ENTER')

k = tvm.reduce_axis((0, K), 'k')

C = tvm.compute(

(batch_size, features, M, N),

lambda yb, yf, m, x: tvm.sum(A[yb, yf, m, k] * B[yb, yf, x, k], axis = k),

name = 'C')

D = topi.broadcast_add(C, ENTER)

Batch matmul and transpose fusion computation can be declared as:

# computation representation

A = tvm.placeholder((batch_size, features, M, K), name='A')

B = tvm.placeholder((batch_size, features, K, N), name='B')

k = tvm.reduce_axis((0, K), 'k')

C = tvm.compute(

(batch_size, M, features, N),

lambda yb, m, yf, x: tvm.sum(A[yb, yf, m, k] * B[yb, yf, k, x], axis = k),

name = 'C')

Fusion Kernel Performance

The shape of [batch=64, heads=8, M=1, N=17, K=128] is chosen to elaborate the performance of the generated code. 17 is chosen as the sequence length since it is the average input length in our production scenarios.

- tf-r1.4

BatchMatmul: 513.9 us - tf-r1.4

BatchMatmul+Transpose(separate): 541.9 us - TVM

BatchMatmul: 37.62 us - TVM

BatchMatmul+Transpose(fused): 38.39 us

The kernel fusion optimization brings a further 1.7X speed-up.

Integration with Tensorflow

The input shape of batch matmul in our workload is finite and can be enumerated easily in advance. With those pre-defined shapes, we can generate highly optimized CUDA kernel ahead of time (fixed shape computation could bring the best optimization potential). Meanwhile, a general batch matmul kernel suitable for most of the shapes will also be generated to provide a fall-back machanism for the shapes which does not have a corresponding ahead-of-time generated kernel.

The generated efficient kernels for specific shapes and the fall-back one are integrated into the Tensorflow framework. We develop fused ops, such as BatchMatMulTranspose or BatchMatMulAdd, to launch the specific generated kernel using TVM’s runtime API for certain input shape or invoke the fall-back kernel. A graph optimization pass is conducted to automatically replace the origin batch matmul + add/transpose pattern with the fused ops. Meanwhile, by combining a more aggressive graph optimization pass, we are trying to exploit TVM to generate more efficient fusion kernels for the long-tail operation patterns to further speed up the end-to-end performance.

Summary

Inside Alibaba, we found that TVM is a very productive tool to develop high performance GPU kernels to meet our in-house requirements. In this blog, NMT Transformer model is taken as an example to illustrate our optimization strategy with TVM. Firstly, we locate the hot-spot of Transformer model through first-principle analysis. Then we use TVM to generate highly optimized CUDA kernel to replace cuBLAS version (13X speed-up is observed). Next, we leverage TVM’s kernel fusion mechanism to fuse the preceding/following operations of batch matmul to bring further performance improvement (with further 1.7X performance improvment). The end-to-end performance improvement is 1.4X. Based on those generated kernels a graph optimization pass is developed to replace the original computation pattern with the TVM fused kernels automatically to ensure the optimization is transparent to end users because as AI infrastructure provider we found that transparency of optimization strategy is very important to popularize its adoption. Last but not the least, all those optimizations are integrated into TensorFlow in a loosely coupled way, demonstrating a potential way for integrating TVM with different deep learning frameworks. In addition, there is an ongoing work to integrate TVM as a codegen backend for TensorFlow, we hope in the future more results could be shared with the community.

Resources

References

[2] nvprof is Your Handy Universal GPU Profiler

[3] Add Loop Invariant Node Motion Optimization in GraphOptimizer